360 Seconds - Grandma's Plate

/Grandma’s Plate

A 360 Second Residency • May 29th, 2020

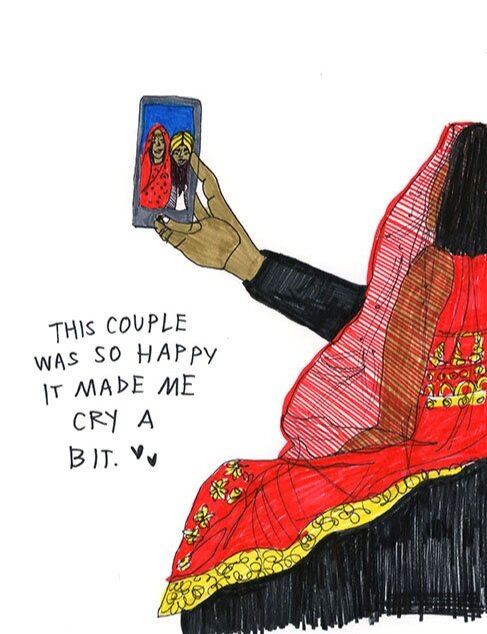

At the end of May, we put a call out for a flash 360 second residency for the last weekday of our CSA theme on Food. In NYC, the city was still under quarantine. It was also the week of George Floyd’s brutal killing in Minneapolis and cities were newly on fire with the rage of centuries of brutality and racism.

We decided to put out a call to connect to memory and lineage– to connect to our histories as we reflect on where we stand today.

Food keeps us grounded to place, lineage, circumstance. Food and memory are often braided together in the same breath. Revolutions have begun over the price of bread. Feuds have started over cannoli recipes and whole peoples have been killed over fertile land, sugar and spice. Most delicious things have complicated origins. Yet what feeds us out of necessity and what feeds us for the pleasure of eating intersect across cultures and time. Grandmothers have often held history not of books but of the lived day to day– in what is on the plate.

The directions were simple: Take six minutes to write about a dish your grandmother would have made or eaten, real or imaginary.

Here are some of the reflections:

Tina West

My grandmother cooked like she wanted her Black card revoked, and I’m so jealous of all the Black kids who talk about their grandma’s collardgreensgritscornbreadhamhockcobblersblackeyedpeashoppinjohnchitlinssweetpotatoespotatosaladfriedchicken. But I did get to eat mulberries right off the bush in her backyard. And one year, we made vanilla ice cream from snow. And I liked how she made my eggs, runny with lots of hot sauce.

JK Lilith Canepa

She made rugelach and blintzes. My mother never taught me how to do either. Well yes she did. But my mind was elsewhere, wherever it goes. So here's my re-creation:

Rugelach - we called them horns. You cut the dough into rectangles or maybe wavy rectangles and put poppy seeds inside. See my relationship to the poppy goes back generations. Or was it jam? And twist and roll them into little cornucopia (cornucopi?) copae? and bake them. However long.

Blintzes - well, I didn't like eggs as a kid or tomatoes. My favorites today, go figure. Another rollup food. And I didn't like farmer cheese either. But the blintzes, oh so good.

And Grandma Nettie, my father's mother, she who must be obeyed - see she's connected too because she now grows in my garden with all her prickly power - she would fry chicken skin with the fat attached till it got crispy and we would gobble down the grebenes sometimes with little feather hairs still attached. Or the fat itself on matzoh, lots of salt. How did they make it into their 80s? How will I? Oy!

Deepti Zaremba

Great Grandmother Lydia: “We are not strong because we had to be;

we are strong because we are."

Two Recipes: Just Because

Dandelion Wine

Wild Blueberries, sugar and flour, a thick glass pie plate, a generous butter crust -- baked into a delicious jam pie

Dandelion Wine comes from Hazel Van Woort, my five-times-great grandmother. She was a brewer and ran an inn with her husband on Long Island near Saint John, New Brunswick, Canada. Her recipe for Dandelion Wine was so important my great-aunt (grandmother’s sister) wrote it down three times in her hand-made cookbook. Of course, there were barely any measures, and it was never specified — dandelion flowers? or leaves?

I found dandelion leaves at Russo’s (farmer’s market) and made two batches of wine. Pretty horrible, unless you mixed it into heavily sugared strong black tea. Then the miracle of a spring tonic opened up, as it forced energy to flow through all the channels.

Blueberry pie — the tiny tiny wild blueberries that grow everywhere in New England and eastern Canada. Great-Aunt Lena was lucky not to lose her pail or wet her pants as she backed away, downwind, and then fled home, away from the bear. All creatures love blueberries.

My mother sent me out with Aunt Lena’s pail, and 10 year old that I was, I ate most of the berries before I got back to the cabin. I felt so ashamed when I realized Mom had fired up the wood stove, prepared the butter crust, and was just waiting for that tart, sweet, bounty to fill the whole family.

Through these two recipes I have learned the wisdom of the grandmothers: the earth is generous; it is important to share.

Patricia Miranda

My grandmother Emenigilda Eugenia Glorinda Fungaroli Miranda had two signature dishes that were a bit different than your typical Italian fare. Her family was from Sud-Tyrol, in Northern Italian Alps, in Trentino Alto Adige. The most important one was Nonni's rice (Nonna for grandma, affectionately Nonni in our family). Instead of pasta, she cooked rice in chicken stock and served it with her homemade tomato sauce. We would flatten the tomatoey rice into a circle and eat it in quarters like pizza. We had pasta too, lasagna, eggplant, ziti, but Nonni's rice was her main fare. The other dish was Canederli in Brodo. These were dumplings with Italian salami in chicken broth, a Tyrolean dish. The taste is so particular, if you don't have the right salami it just isn't right. Nothing else tastes like it. Canaideles were always served first before the past or rice, then the meat and vegetables. Ciao Nonni.

Alex Gray

Nell Silk. According to the few precious photos she was wiry, birdlike, always moving, doing for others - or so I imagine. Hell, she raised seven children; there’s no way she wasn’t a tornado of movement with arms always full of cascading tasks. I imagine her in the kitchen, cooking for the family while shooing away any child who bothered her, who came in to plead their case and held up her work. Asking the older ones to take the younger ones away - please - they are under my feet! And this is a hot. pan. I imagine she made a nice pie and mash or Sunday roast. That she’d do a fry-up on a weekend or a nice piece of fish on a Friday, carefully selected at the local mongers. Nell tended to others - that I know. She took food to those in the neighboring streets who couldn’t feed themselves. She shared - portioned out what little the family had by wrapping it in cloth or carving off a bit to give away. Through World War II and the long rationing years that came after, she saved everything: the fat from the meat, the ends of the vegetables, the heels on the bread. I imagine Nell could alchemize magic from those scraps. That no matter how harsh it seemed when she pushed you out to play in the street with the others, when you returned at dusk - hands dirtied, lungs bursting from a come-home-now-or-else sprint down the high street - and stepped through the doorway, you’d be welcomed by a brisk Where’ve you been? Wash your hands and sit down, and then? Comfort. Warmth. The knowledge that any meal placed in front of you was composed with thought and care. If Nell was at home, you knew you were loved.

Dhira Rauch

A fable that might be true.

I imagine she wished more than she made

a dish with anchovies garlic and capers

something she would never eat

to save her breath and her skin- a sure giveaway that she was not only Italian, but Sicilian

dirty until dirty was branded cool by Coppola

dirty til the blood on the hands was worth more than the grime.

A pasta made by hand with the old flours- from Ragusa- soft wheat, like frumped hats, and ripe tomatoes, picked in the morning. But she never was able to find tomatoes like that in Chicago in the 20s. Or basil even. Much less anchovies.

Or a fish she could salt and stick fennel and lemon inside. A fish so fresh the firmness would feel perverse. Eaten on Fridays of course because of God. But really because it was good.

Better than God, but she’d never say so. She didn’t cook for everyone the way her grandmother would, because this was America- the freedom to be lonely and have to go work at the House of Fabrics while your husband did errands in a milk truck that sometimes didn’t come home. Instead it was lamb chops with mint jelly and Jello salad. All the wiggling gelatin of dead hooves. The real Horse power of America.

But I imagine in her meal of meals she’d let herself breathe her salty fishy breath and drink red wine til it didn’t matter and eat cannolis and not worry about her frail heart and her half-life in this country, so far from the morning when the tomatoes were picked.

“My grand food was greasy.”

Natasha Corbie

Julia Meeks

Beets. It's easter season. There's a honey roasted ham ordered for pick up. But I'm starting my salvation for my Nana's beets. Red onion: Raw, pickled. Boiled Beats: whole. Boiled Potatoes: yukon, quartered or eighthed. Carrots: steamed al dente. Green Beans: the same. FRESH MINT. It wasn't just the recipe, but the care. The selectivity of each root, every leaf. The careful salting pinch by pinch, always perfect. Each vegetable given Its own ritual transformation, cooked to Its own perfection. Not alone in what attention, what care ! it received. Veggies removed from steam, from boil, left to cool on the wooden board. Cut when warm. The dressing marinading the onions– Olive Oil: extra virgin, Red Wine Vinegar: tart, Salt– drizzled over each corner, every peak, every valley, of each hand placed quarter or whole in the deep tray. A stir as if life depended on it. Because it does. Fresh mint leaves: whole.

It's everything.

*post note: Since my grandmother passed, I have made this recipe three or four times, also for her life celebration to share with the famiglia. A similar beet (and onion only) salad can be found at Brancaccio's on Fort Hamilton Parkway, just ten or so minutes from where she grew up in Brooklyn. Hallelujah. But still, there's no plate like Nana's.